“Wildness and madness has always been my motto”

Henning Rud Andersen is no ordinary researcher and cardiologist – just ask Arnold Schwarzenegger, Henry Kissinger or Mick Jagger. Meet the professor who will be celebrated with an honorary symposium on 21 April.

CELEBRATION ON FRIDAY

Come to the honorary symposium for Henning Rud Andersen on Friday 21 April 2023, in Aarhus University Hospital’s Auditorium A G206-145, Palle Juul-Jensens Boulevard 99.

“It took me two and a half years to take a commercial education in Himmerland. But then I found out that it wasn’t much fun. Unfortunately, I wasn’t bright enough to go to secondary school, so I took a lower secondary course in evening classes for two years, and then an upper secondary course in Odense.

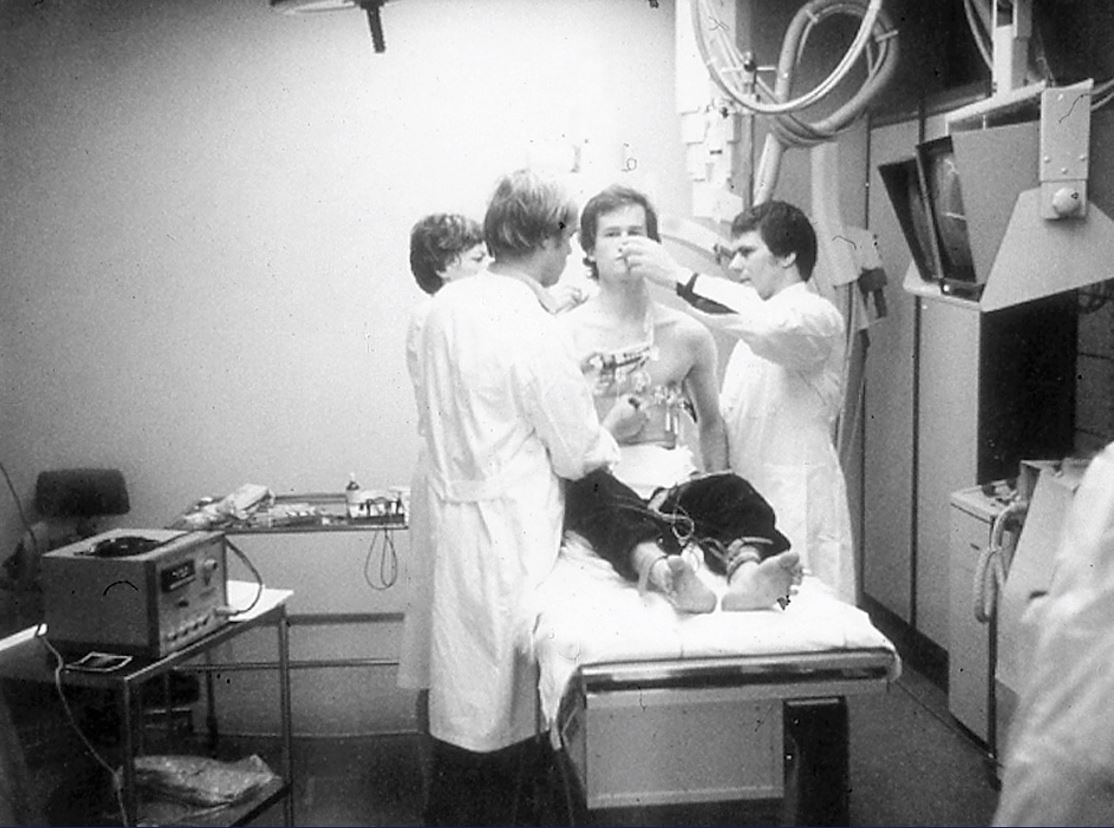

As a medical student, I met a professor who became my mentor. Jørgen Fabricius was a cardiologist, and he was an amazing researcher, full of madness and wildness. I wanted to be like him. The first thing I did with him was to invent a new pacemaker model that stimulated the heart from the oesophagus. I made it myself from urinary bladder catheters, swallowed it and stimulated my own heart up to 150 beats a minute while I lay there on the hospital bed. I was in big trouble when I told Jørgen that I had sneaked into his heart laboratory the previous night and tried to do it myself. He walked around and around the office and was completely red in the face from anger, but he also thought it was incredibly funny. We agreed that I wouldn’t try the pacemaker again without him being there.

Then we acquired ten guinea pigs – these were porters and students, who were each given DKK 500, cash in hand. In those days you weren’t required to ask permission of the National Committee on Health Research Ethics, so all ten of them were given bladder catheters with balloons and electrodes down through the oesophagus. They bled a bit from the nose. We two medical students were the sole authors of that study, and I got my first world patent. That’s how my research career started.”

“Wildness and madness, I’m all in favour of it. That and civil disobedience. That’s my motto, and I’ve always been like that. When I got a job in Aalborg in 1984, I decided to write a higher doctoral dissertation. I persuaded the lab technicians to take extra electrocardiograms from the patients’ right-hand side around the clock, to examine the damage to that side of the heart. I got thousands of cardiograms, and I received the hearts of those who died. That meant I could examine whether there were any blood clots or other effects on the right ventricle, and compare it with the cardiogram.

I ended up with the brains of 107 Aalborgans in formalin, in yellow buckets. They had all come to the cardiology department with suspected blood clots in the heart, but of course I wasn’t always there when they died. So to get the bodies transported from the chapel in the south of Aalborg to the Department of Pathology, I bribed the chapel assistants.

You can get a long way by giving people lots of praise, a bag of beers, a Red Aalborg and sandwiches every Friday. When one of ‘Henning’s bodies’ arrived at the chapel, there was a yellow mark on the paper, which meant that the chapel assistants had to make sure that the body was transported by hearse to the Department of Pathology. Then at the weekends and in the evenings, I met up with a pathologist, Professor Erling Falk. We had a transistor radio, a packed lunch and a thermos, and we took the hearts out. My children sometimes came in and ate dinner there, because I was never home. Today, the records are activated in the Provincial Archives in Viborg. They’ve been used for thorough research and have resulted in a higher doctoral dissertation. The hearts themselves were disposed of. Today, it would be completely impossible to do 107 cardiac autopsies in two years, because the relatives would refuse permission.”

“I was at a conference in Phoenix, Arizona, when I had the idea for my greatest invention in a split second – the catheter-based heart valve, TAVI, which can be inserted into the heart via a vein in the groin. This was in 1989, and I was sitting listening to American researchers talking about how they could insert thin metal grilles into the coronary arteries in the heart to prevent new blood clots forming.

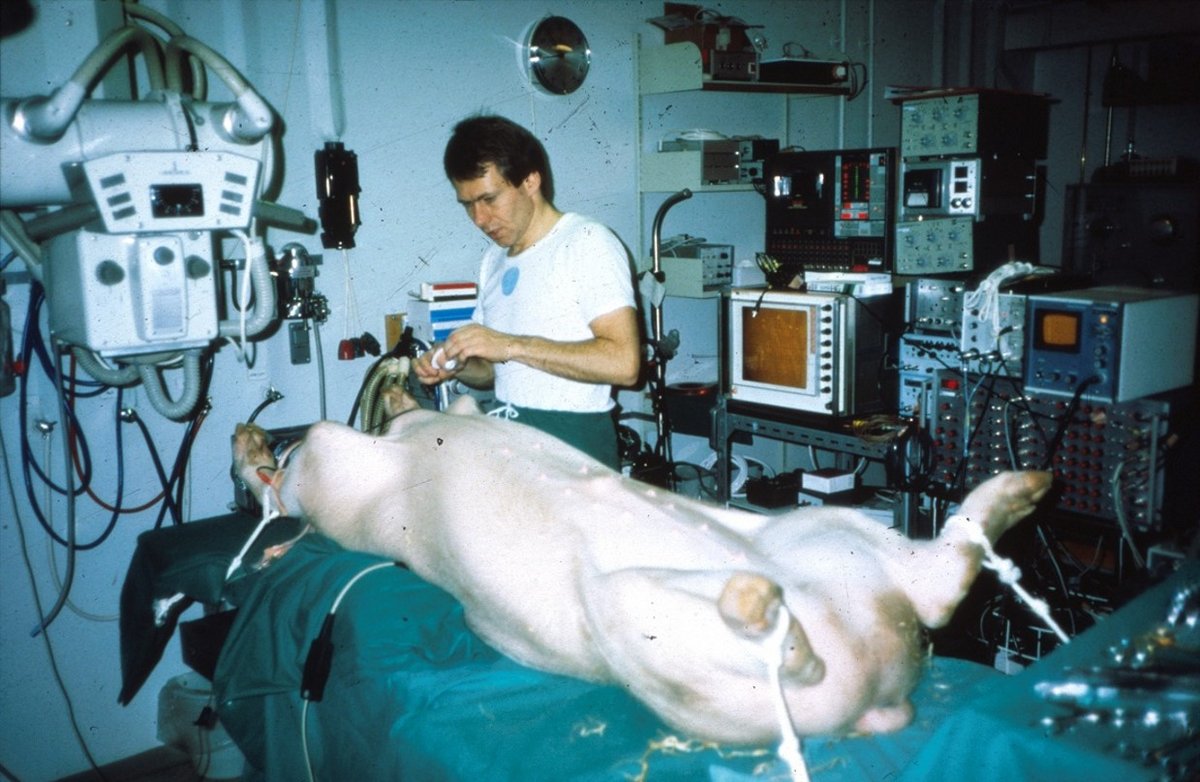

And suddenly I decided that I would be the first surgeon in the world to insert an artificial heart valve without an operation. Two and a half months went by before I could try it on a pig. When you get a good idea, and you’re passionate about it, you don’t have the patience to wait. I bought lattices from a builders’ suppliers and hearts from a butcher’s shop, and I used balloon catheters from the Cardiology Department, and I made a heart valve by hand. I had no animal ethics approval and no pigs, but my colleague the cardiac surgeon Michael Hasenkam was experimenting with surgically implanting heart valves in pigs, so we began working together. My dogma was that I was not allowed to stop the heart, and I was not allowed to touch the chest. I was 38.

In 1992 the invention was published in the European Heart Journal, but it wasn’t until twenty years later, when the French surgeon Alain Cribier implanted my artificial heart valve in a human being – and the patient survived – that investors became interested. Today, the invention consists of a metal framework, to which biological tissue from a calf is sewn.”

“Mick Jagger has received one of my heart valves. The Rolling Stones had to cancel a tour because he became ill, so he was given one in New York.

Arnold Schwarzenegger got one in Cleveland – I know the professor over there who treated the Terminator. Henry Kissinger was treated by one of my good colleagues at Columbia University Medical Center in New York. My own father was walking around the same afternoon that he received one, and he was home again after 2-3 days.

This week alone, we have implanted eight heart valves at AUH. In the Western world, a total of 2.5 million heart valves have been implanted – we have no data from Asia. My world patent has expired, but I have no financial worries for the rest of my life.“

“You have to take the beatings you get. A lot of people laughed at me and said that Henning had gone nuts. But it gives me a good feeling in my body that I’ve been fortunate enough to be able to leave my mark. Inventions may fade away, but this one will be around for many years to come. When I’m gone, my children can remember that their dad did this.”

“Nobody expects anything from me any longer. Yesterday, I was in the operating theatre while four implants were inserted, but I don’t interfere with the technical side of things. After all, I’m not employed at the hospital, and I’m not allowed to do anything medical.”

“All my life I’ve been married to my work, so I’ve been a bad father. I travelled a lot, and several times a year I was on work-related trips to the USA. I rented a red Corvette and drove around California. So that cost me something in the family area. But I’ve done a lot to maintain a good relationship with both my ex-wives. We can spend Christmas together, all three of us.”

“I had two brain haemorrhages at 7-8-month intervals. They both happened while I was in the operating theatre implanting a catheter in patients. A nurse saw that I was unwell and brought me out to the coffee room, where I had a seizure. It was a congenital defect, a so-called aneurysm, and I couldn’t just live with a time bomb like that, so I had brain surgery.

Dead tissue had to be removed from the left side of the brain, close to the language centre, so there was a risk was that I might end up unable to speak or understand what people said when I woke up. But the operation went perfectly. Since then, though, I haven’t been allowed to implant a catheter. I understand that completely, although I miss it. I wouldn’t want to put myself on the table for a surgeon who has seizures.”

“I used to run a lot, but now I’ve bought an electric bike and walk with a cane, because I got acute rheumatoid arthritis a year and a half ago. I’m pleased that it came so late in life, though, because if it had come when I was in my 30s, I would not have been able to use my hands as a doctor. Otherwise, I ride around in my electric Porsche. I’ve also just bought a 1943 Willys Jeep from the time of the Second World War.”

FACTS - Henning Rud Andersen

- Born in 1951.

- Grew up in Himmerland, where he received an education in commerce.

- In addition to his upper secondary school leaving examination he received an MSc in Medicine in 1982 and a DMSc in 1991.

- After studying in the heart wards of the University Hospitals of Odense and Aalborg, he transferred to a research position at the former Aarhus Municipal Hospital.

- In 1996, he was employed as a consultant and later professor at the Department of Cardiology, Section B, Aarhus University Hospital.

- He has gained international recognition for the invention of the catheter-based heart valve, TAVI, which can be inserted into the heart via a vein in the groin.

- He was behind the ground-breaking DANAMI-2 study from 2003, which showed that patients with a blood clot in the heart benefited more from balloon treatment than from blood clot-reducing medicine – and that the former resulted in a persistent and significantly lower risk of death from coronary disease or a new blood clot in the heart. The study has meant that the treatment of people with a suspected blood clot in the heart starts right from the ambulance.

- He has published a number of research projects and more than 170 medical articles, and has received a number of honorary awards, including the Danish Cardiology Society Research Award, the Aarhus University Anniversary Foundation Science Prize (2003) and the Hartmann Brothers Memorial Prize (2009).

- He has two ex-wives, six children and six grandchildren.

- He lives in Højbjerg, Aarhus.

CONTACT

Professor Emeritus Henning Rud Andersen

Department of Clinical Medicine – Heart and Circulation

E-mail: henning.rud.andersen@clin.au.dk